The Hogarth Frame

A brief note on the ‘Hogarth frame’ to coincide with the London Original Print Fair,

4 -7 May 2017, held at the Royal Academy of Arts, London

We can readily conjure up an image of the ‘Hogarth Frame’ – that ubiquitous narrow black frame, likely taking its name from the framers and print sellers Joseph Hogarth & Sons, who throughout most of the 19th century churned out a much debased version of the ‘Peartree frame’ used by William Hogarth for his prints. Common terminology, though convenient, skates over detail and that which is interesting.

Mr Garrick in the Character of Richard the 3d, 1746. Engraved by William Hogarth & C. Grignion, in original ‘Peartree’ frame with carved and gilded slip. Andrew Edmunds, London

Typically the ‘Hogarth frame’ is straight sided with finely grouped mouldings. The best of which are run in ‘Peartree’ which takes the detail and stain well due to its close smooth grain. The moulding is laminated to a mitred pine back frame glued and pinned together. Some are ‘keyed’, with a tapered and wedge shaped spline of wood inserted across the mitre joint for added strength.

English Eighteenth century ‘Peartree’ frame, pine back frame, mitred and keyed construction

More commonly, but less fine, the frames can be made in pine – though this lesser quality has not always been understood. The diarist John Evelyn, writing in 1664 in his treatise on wood, Sylva, described the wood’s qualities as ‘exceedingly smooth to polish on, and … equal with the Pear tree’[1]. However, Stalker & Parker in A Treatise of Japaning and Varnishing, 1688, wrote, more correctly, that ‘japaning’, or blacking, the pine moulding is ‘very troublesome; and … not so cheap or valuable’[2] – understanding that the laborious process of ebonising can never bring pine up to the quality of the closer-grained ‘Pear-tree’, which is the best.

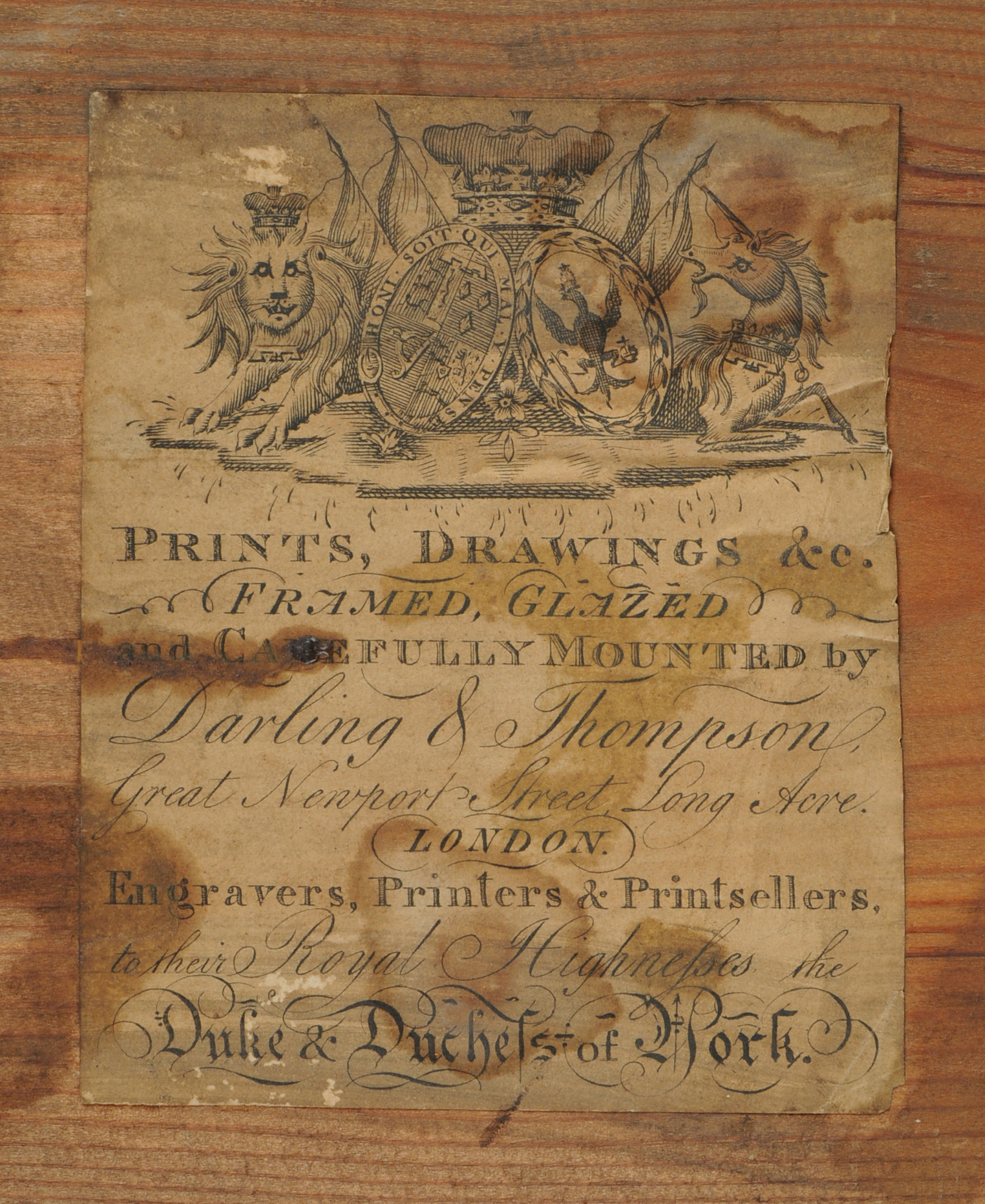

Eighteenth century ‘Peartree’ frame, Darling & Thompson, Great Newport Street, Long Acre London; Engravers, Printers & Printsellers to their Royal Highnesses, Duke & Duchess of York.

The more decorative print frames are enriched with carved and gilded inner, and or outer, mouldings and sometimes with gilded cast lead ornaments pinned to the corners. The addition of a carved and gilded inner slip, with leaf sight moulding and a frieze textured with gilded sand, not only serves the practical purpose of separating the glass from the print but also makes the frame wider and grander and by so doing elevates the status of the print to compete with the painting.

Eighteenth century ‘Peartree’ frame with gilded lead corner ornament

The framed print gained popularity in the 17th and 18th century as they were cheaper than paintings – becoming the economic decoration of choice for the emerging and expanding middle class. John Evelyn even wrote to fellow diarist Samuel Pepys in 1689, urging him to buy prints because they could be procured at a very ‘tolerable expense … [and] some are so very well done to the life that they may stand in competition with the best paintings’[3]. Interestingly, Pepys made a diary entry noting ‘This morning comes Mr. Lovett, and brings me my print of the Passion, varnished by him, and the frame black, which indeed is very fine.’[4] He clearly enjoyed the process of acquiring and framing his prints, noting in his diary on Friday 30th April 1669: “Thence to the frame-maker’s one Norris, in Long Acre, who shewed me several forms of frames to choose by, which was pretty, in little bits of mouldings, to choose by.’ [5]

It may seem like the ‘Hogarth frame’ has less relevance today. With the rise in popularity of larger and more brightly coloured contemporary prints, a variety of framing styles and quality have emerged, meaning this particular aesthetic of framing could be outmoded. But perhaps the ‘Hogarth frame’ is not without its influence.

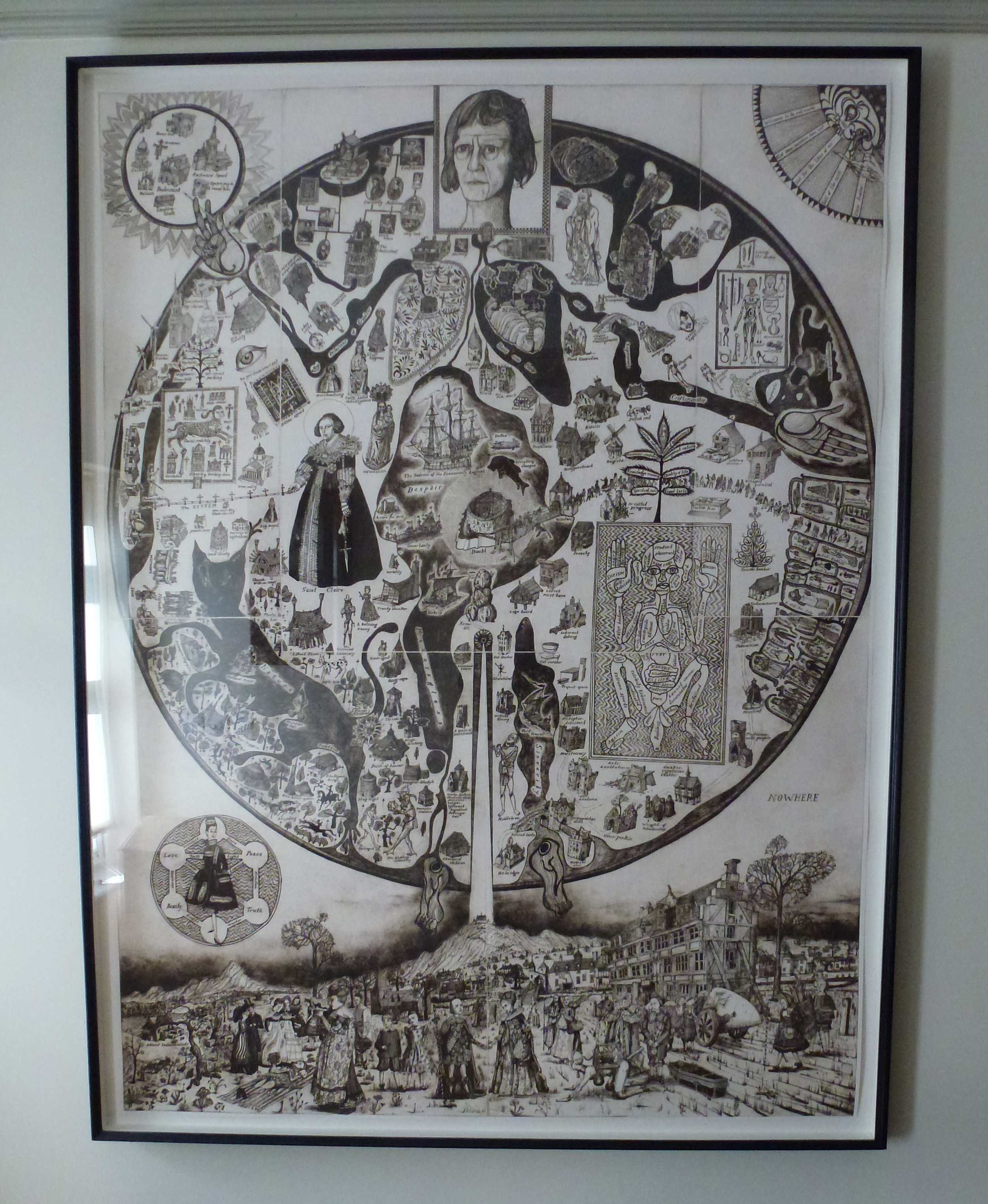

Grayson Perry Map of Nowhere, 2008. Etching from five plates. Private collection

Grayson Perry chooses to frame his etchings in a narrow black moulding reminiscent of the ‘Hogarth frame’, though for the editions printed in a single colour the frame, with a modern quirk, is coloured to match.

NOTES

1. Mason, Pippa, 1992, ‘Framing Prints in England 1640-1820’ in Museum Management and Curatorship Vol 11, p 118

2. Stalker & Parker, 1688, A Treatise on Japaning and Varnishing, p.36

3. Mason, Pippa, 1992, ‘Framing Prints in England 1640-1820’ in Museum Management and Curatorship Vol 11, p 120

4. Mason, Pippa, 1992, ‘Framing Prints in England 1640-1820’ in Museum Management and Curatorship Vol 11, p 121

5. Mason, Pippa, 1992, ‘Framing Prints in England 1640-1820’ in Museum Management and Curatorship Vol 11, p 121